Mother of author Kekla Magoon was “very proud” when her daughter learned to read at the age of two. However, she was not aware at the time that her daughter would go on to write eight young adult novels and receive two Coretta Scott King awards.

Magoon wrote her first novel in high school and later moved to New York City to pursue writing. She currently lives in Vermont, working as a full-time writer, writing teacher and speaker. She travels to libraries and schools around the country to talk about her books. She describes these travels on her website as “awesomely fun.”

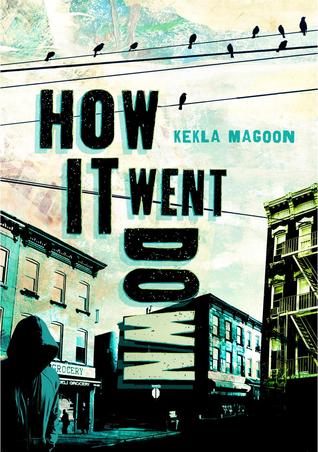

Magoon visited Flyleaf Books in Carrboro on July 20 to discuss her 2014 novel How It Went Down and the issues that surround the book’s plot.

The book, published in 2014, has since received critical acclaim and awards including the Coretta Scott King Book Award in 2015.

She began writing the book in 2012, following the shooting death of black Florida teen Trayvon Martin.

How It Went Down centers around the story of a black teen named Tariq Johnson, who is shot and killed by a white man. The novel is composed in a series of vignettes, in which 18 community members share their opinions of Johnson and recount their versions of the shooting.

“It’s fiction,” Magoon said, “but it’s based upon very real issues of bias and violence in our society.”

How It Went Down is one of eight young adult novels Magoon has written, several of which deal with the issue of racism.

“I believe it is vital for young readers to be engaged in the ongoing social dialogue about race, bias and violence,” Magoon said. “Teens are constantly subject to the pressures of these social dynamics and rarely invited to the conversation about them.”

The accounts of the book’s characters often do not match, and Magoon says this is purposeful to put importance on individual voices and perspectives throughout the story.

“My message, if there is one, is to question the nature of ‘truth’ and who has the power to determine the truth of a narrative,” Magoon said. “Each of my characters tells their own truth, and yet their stories do not agree. The charge to the reader is to sort through information and form an idea of their own, because the voice of each reader is as important as the voice of the author.”

Chapel Hill media specialist SaCola Lehr agreed that characters’ voices are important, especially in pieces of literature that deal with social justice issues.

“Authors give voice to characters or people who can no longer speak for themselves or whose voices are not being heard,” Lehr said.

Magoon commented on how the uncertain ending of the story connects to that of real-life crimes and contributes to the story’s message about individual viewpoints.

“This is a book about questions, not answers,” Magoon said. “It is about the gray areas between what is black and what is white.”