Chapel Hill’s high schools desegregated in 1966. Are we integrated?

That was the question posed by senior Will Blyth in a Proconian editorial published on May 15, 1975. His answer, as well as that of guidance counselor Vivian Edmonds and principal William Strickland, was “no.”

Edmonds commented, “as far as a truly integrated school goes—we don’t have it.” It had been just a decade since Lincoln and Chapel Hill merged, moving black students to the school from which they had previously been barred. “Integration will happen,” Strickland said. Blythe’s article concluded: “The obvious question that remains is: When?”

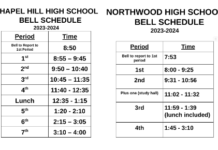

Another four decades have passed, and that time still may not have arrived. The number of African Americans in my classes this year could be counted on one hand, underrepresenting the 12% of black students in the school. Low-track (standard) courses contain primarily lower-income and minority students, while upper-track (honors and AP) classes have more socioeconomically advantaged students.

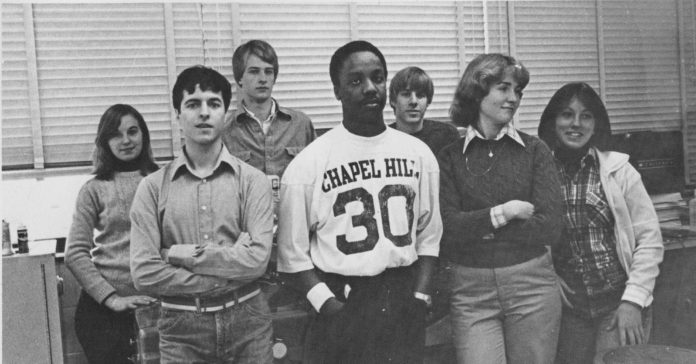

Racial divisions have been a recurrent concern at the school. Proconian wrote on March 9, 1990: “Since the Proconian is the sole source of news and editorials at CHHS, it is important that the diversity of the students here be well represented on the newspaper staff. Unfortunately, such is not the case this year, so we strongly encourage anyone, especially minorities, to use the paper as a forum,” about racial uniformity at the school newspaper:

Chapel Hill has had issues relating to race just like the entire country. Mr. Hollingsworth knew this even in 1933, and spoke about it to the school’s Hi-Y club, affiliated with the YMCA. “The white person is responsible for the clashes between these two races,” the Proconian quoted Hollingsworth. “There will be a time when, socially and economically, the white man and the Negro will be on the same level.”

It has been fifty-one years since Chapel Hill’s desegregation, and though things have improved, they have not come far enough.