QSA at 25: Part Four

This article is the fourth in a series of articles examining the founding and legacy of the Queer-Straight Alliance at Chapel Hill High School.

Walkmans roamed the hallways, Game Boys were played under desks in class and students were at a turning point in social justice—in 1993, Chapel Hill embarked on a new chapter for the acceptance of homosexuality in society.

The year would prove to be pivotal for the bustling school, as a battle over lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) education was about to break out, causing hundreds of residents to question what they believed in.

The multicultural project in David Bruton’s English class gave students the opportunity to select pieces of literature from different cultures and communities to read and analyze. The project’s creation in 1993 would cause a district-wide debate over education on LGBTQ issues in the classroom.

“The school board was encouraging schools and teachers to integrate multicultural perspectives into the curriculum. I was teaching mostly American literature. The United States is a nation of immigrants (as we, of late, seem to forget) from many cultures,” Bruton said. “Between the activities of Cultural Awareness Sensitivity Educators (CASE) and my participation in it and the board’s request, my independent study American Multicultural Literature Project was born.”

The first signs of opposition arose when student Lindsay Little spoke out against the gay literature portion of the project, asking to be transferred to another class. The works by gay and lesbian authors were optional, as students could choose among a large number of fictional and nonfictional titles, including works by African Americans, Native Americans and other groups.

“My religion teaches that sex should only occur between a husband and a wife and that any other sexual relation is wrong,” Little told the school board in a meeting protesting the project in October 1993.

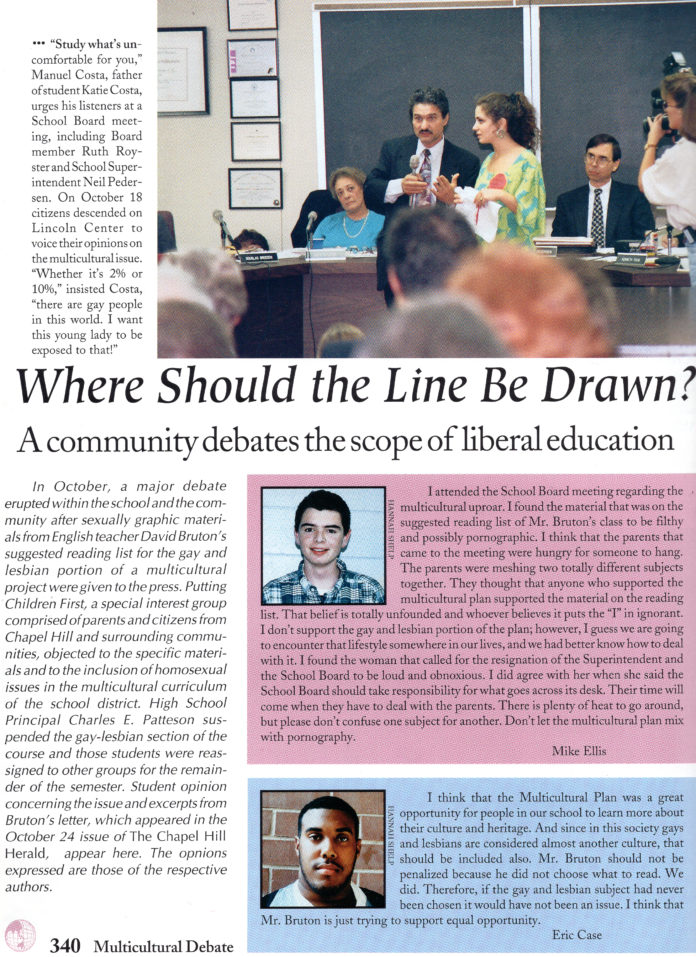

Special interest group Putting Children First, comprised of local parents and community members, also attended the meeting to speak out against the gay and lesbian literature included in the project.

Chapel Hill student Mike Ellis, who attended the school board meeting, disagreed with parents’ calls for then-superintendent Neil Pederson to resign, but expressed distaste for the gay and lesbian portion of the project, according to his comments appearing in The Chapel Hill Herald on October 4, 1993 and later reprinted in the school’s Hillife yearbook.

Ellis stated that the school board should have taken more “responsibility” in identifying the multicultural project’s gay and lesbian reading suggestions, deeming them “filthy and possibly pornographic.”

“Don’t let the multicultural plan mix with pornography,” he warned.

Little, along with other students in opposition to the project, was ultimately kept in Bruton’s class since students were not obligated to read the LGBTQ material.

The school board meeting did not mark the end of the backlash, however, as Little would inspire others to criticize the readings, some with more force than her testimony. The wave of violence and bigotry that awaited Bruton had barely begun to surface.

In addition to the students, faculty members felt the need to weigh in on the controversy. In a 1994 issue of Proconian, one teacher anonymously commented that “Bruton’s [curriculum] is a powder keg ready to explode. Anything could happen.”

Students also uncovered that Bruton himself was gay, leading his critics to attack the teacher personally.

“I am not a crusading social activist. I was never an ‘out’ gay man. I neither desire nor seek publicity, but when things happen that can cause the lives of young people to be more difficult or to hurt them, I cannot stand by and do nothing,” Bruton said.

The harassment was startling to several members of the school community.

“This was one of the first times I was aware of in which there was pushback from people and parents who weren’t comfortable with [the class material],” former Chapel Hill history teacher Al Baldwin said. “I think [students] saw it for what it was, a personal attack.”

Chapel Hill student Katie Costa, alongside her father, spoke in support of Bruton at the October 1993 school board meeting.

“The sexual performance between two consenting adults does not make my stomach cringe, but the blatant discrimination and alienation of a wonderful teacher does,” Costa toldThe Chapel Hill Herald following the meeting.

After Bruton’s sexuality became apparent, students arrived on campus to find homophobic graffiti spray-painted onto the sidewalk, school building and several school buses that drove around town one morning. In Bruton’s classroom, vandals threw rocks through the windows, leaving broken glass strewn across the floor. A dead possum was also thrown into the room.

“The harassment of David Bruton brought the conversation into the public both at school and in the community,” Mary Gratch, who was a counselor at the time of the incident, said. “We knew that more had to be done.”

With the harassment came the renaming and official formation of the school’s previously informal LGBTQ issues club that had begun meeting in the early 90’s: the Gay-Straight Alliance. As Gratch explained, the club now had a purpose: to protect vulnerable students and erase the bigotry which had been apparent in Chapel Hill over the past school year.

In reaction to the community’s fight against gay representation in schools, local members of the LGBTQ community held a conference entitled “Opening Doors: Understanding Issues of Sexual Orientation in the Community.” The conference took place October 1, 1994. With an audience of over 200 people, members of the the community came together to discuss issues facing the LGBTQ community at the time.

Ultimately, the multicultural project scandal was quieted with the district school board’s passing of the Multicultural Action Plan, a system that subjected all multicultural material to screening by district officials.

The plan also set a formal complaint process into place for students, faculty and parents to file any problems they might have with classroom material.

“The [guidelines] leave the choice of curriculum material up to the teacher,” Mary Bushnell, a school board member at the time, said. “Material will only be screened if a complaint is raised.”

The irony of the situation was not lost on Bruton or his supporters.

“All of the groups in the project have endured protracted periods of socially sanctioned oppressions and discriminations,” he told Proconian. Sadly, the trend would continue, as LGBTQ acceptance had yet to become widespread in Chapel Hill.