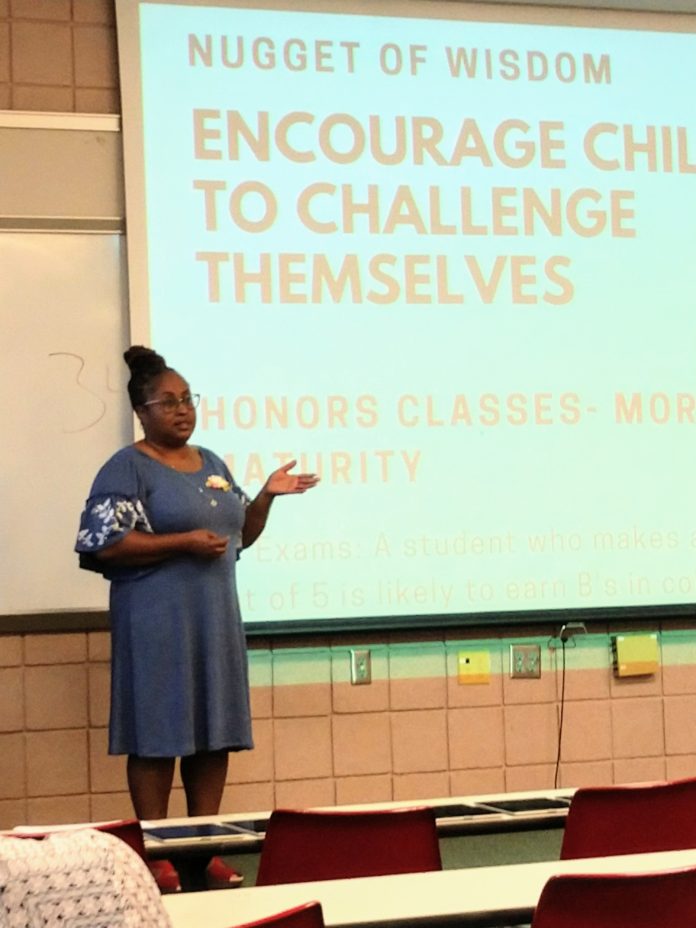

Evon Barnes, an English teacher at East Chapel Hill High School, spoke to parents on May 6 about ways to support their children and narrow the educational achievement gap in Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools, the first presentation in a planned series on the subject.

At an evening presentation at East Chapel Hill, “Closing the Gap—Minority Parents and Community Members,” Barnes gave parents introductory lessons on topics spanning from pre-K to the workforce, including children’s literacy, gifted programs, standardized testing, the benefits of bilingualism and to affordable housing.

“That summit was the first of what will be many,” Barnes said later. “My goal is to provide tools which all parents can use and to help parents understand their crucial role in building a community at home which supports learning.”

In the presentation, she recommended ways to start “giving [children] skills and empowering them” even before they enter elementary school. She said that parents and children should talk openly about and try to align their goals for their child’s future.

Modeling certain behaviors can help a child’s development, Barnes said. As an example, parents of color should get and use library cards for themselves and their children. “What we say to our kids when we don’t use these spaces,” Barnes said, “is that they’re not for us.”

She also commented on why African-American students often do not sign up for Advanced Placement (AP) classes, a point in which the audience seemed particularly interested, though parents there were cordially asking questions throughout.

“Our language [about AP classes] has allowed our children to believe that other people are smarter than we are,” Barnes said, adding that as a teacher who gives classes in East’s Social Justice Academy, she has spoken internally about “intentional recruitment” of minority students in more rigorous classes. “The conversation is being had,” Barnes said.

Several programs in the district—like Blue Ribbon Mentor-Advocate (BRMA), in which volunteer mentors support students from fourth grade on; its associated Youth Leadership Initiative (YLI) club, which does community service projects; and the Minority Student Achievement Network (MSAN) club, teaches about tolerance and justice—have goals of supporting and empowering students of color.

Lorie Clark, the longtime high school specialist for BRMA, who attended Barnes’s presentation, said that while “we encourage” minority students’ enrollment in more rigorous courses, there is a “feeling of isolation” when an black student is the only one in an AP class.

Chapel Hill senior Corrina Johnson, a leader in the MSAN club and member of YLI, agreed with Clark. In one of the AP classes that she took, she said, students would join in the same groups and she would be left. When she is the only black girl in a class, she feels that she has to prove herself.

“It’s just really discouraging when you go into a classroom, and you don’t see someone who looks like you,” Johnson said. “I’ve always been personally encouraged by my family to take honors and AP classes, and that’s not always the case for other black students.”

When Barnes was in high school, science classes in particular plagued her because the language used there was, in her words, “inaccessible to me.”

“I felt that I did not have somebody to help me understand the language,” she said. “If [students] understand the language, they do well.”

That goes for parents, too.

“Educators need to assist parents in decoding language connected with learning,” Barnes said. “After learning the language, and understanding the data, parents can implement a plan to ensure student success.”