Carrboro-based cartoonist Keith Knight always knew he wanted to adapt his decades’ worth of comic strips cinematically but envisioned that the company he would end up working with would be a small, possibly shady, production studio.

However, after spending years in Los Angeles shopping his proposal around, Knight landed a deal with Hulu and was given a chance to dive into a new medium as a co-creator and an executive producer for the show Woke, starring Lamorne Morris of New Girl fame.

“If someone told me, even three years ago, I’d have a show on Hulu with an amazing cast, I’d tell them they’re crazy,” Knight said.

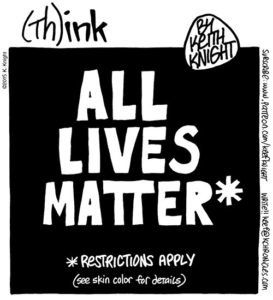

Released on September 9, the show is an eight-episode, semi-autobiographical comedy loosely based on Knight’s weekly comic series the K Chronicles and (Th)ink, containing a hint of surrealist abnormalities and cinematic tendencies with its pristine cinematography and framing.

During the linchpin scene of the series, the show’s protagonist, Keef—a past version of Knight—abruptly has his headphones slapped off his head while stapling flyers around town. He turns around only to see a group of shouting cops with their guns pointed directly at his chest. Not given a chance to prove his innocence, he is thrust to the ground and surrounded by a crowd with cameras drawn. Keef, who up until this point had desperately attempted to distance himself from racial issues in his work, quickly registers that regardless of his attempt to “keep it light,” racial injustice and profiling are looming forces that affect every African-American without exception—a realization that intrudes upon his now frantic mental state.

The scene was directly based on Knight’s experience being profiled by San Francisco police 22 years ago.

Following this, Keef, who was once comfortable drawing the politically safe comic strip “Toast N Butter,” becomes increasingly confused, questioning the comics he’s making and wanting to amplify his voice through his work—or as the show puts it, become “woke.”

“How could we visualize the idea of becoming ‘woke’ in a way that’s unique to a cartoonist?” Keith asked. “The most boring thing to have in a show about a cartoonist would be to have them sitting at a desk drawing, so, how can we make this visually fun as well?”

After some deliberation, Keith and the show’s team of writers decided to have inanimate objects in Keef’s environment burst to life as representations of his subconscious, adding a hint of magical realism akin to the directorial work of visionary Michel Gondry.

As Keef darts around San Francisco, flustered with emotions, the city subtly morphs around him. Viewers may find themselves pointing at their TVs when they see a set of eyes on a mural move. Trashcans, Sharpie markers and Holy Bibles come to life with bulging googly eyes and pressing opinions on what the protagonist should do next. Each with its own animated personality, these fragments of Keef’s clustered mind can jump out at any time, introducing new jokes while simultaneously moving the plot of each episode forward.

In the show’s fourth episode, Keef guides his frustrations into a new project, Black People for Rent, a fake job application flyer that provokes unexpected anger and confusion while leaving viewers with the wrong impression of its intent. Due to the politically bold nature of his comics, Knight is no stranger to controversy that arises from misinterpretations.

“Occasionally, my work shakes things up, and sometimes people interpret it as something not intended,” he said. “It comes and goes. I find that, most of the time, controversy isn’t directly a result of my comics.”

Surprisingly, a large portion of the show’s plot revolves around the protagonist’s experience and the people he meets while walking throughout the city, posting comics and papers or trying to find ways to maintain his financial stability. These seemingly mundane tasks, through the absurdity of the show’s comedy, remain interesting while accurately portraying the daily life of a once young and struggling Knight.

PHOTO COURTESY: KEITH KNIGHT

“I started making my comics in Xerox ‘zines—I copied little ‘zines that I made myself back in the day,” Knight said.” I would put them in little shops around San Francisco. That’s how I got my start, and I will never forget that.”

Although Knight relocated to Carrboro—the first Southern city he presented his comics to—after making connections in Los Angeles, he continued to work on the show, commuting back to L.A., where he attended auditions and writing sessions, and Vancouver, where the series was shot. The show was finished filming by February 28, just a few weeks before the coronavirus pandemic began, but all of the post-production, editing and voice-overs were completed afterwards.

“[Our production] had three different editors whose equipment had to be moved into their houses,” Keith said. “We all had to figure out how to be–I am putting up air quotes–‘in the room with them.’ We also had to send recording equipment to J.B. Smoove and Cedric the Entertainer, who played some of the personified objects. The time difference between L.A. and Carrboro, as well, was a boundary. It was definitely a more difficult process than if we could do it physically.”

Although Knight views Woke as an amalgamation of each writer’s ideas—not solely his product—he made his presence on set and in the show’s creation apparent.

“I was there on the set; I was picking costumes; I was at auditions—I was a large part of [the show’s production],” Knight said. “I have always heard creators sell their work to Hollywood, which then takes it and destroys it. For me, it was important to know that if Hollywood screwed it up, I would be in the middle of it.”

PHOTO COURTESY: KEITH KNIGHT

Knight’s time working on set also gave him rare insight into aspects of film production with which he was unaware before.

“For me, working on Woke was the greatest learning experience,” Keith said. “My management team told me, instead of working on my next project, to just pay attention to every aspect of the production. Since I want to continue as a producer, it was so important for me to understand the whole process of what goes into making a TV show.”

With a length of about 3 hours 24 minutes altogether, the first season of Woke feels more like a lengthy movie you watch over the course of a day or two rather than a full season of television. The elegant camerawork of Ava Berofosky, the deep, blue color palette and the blockbuster-esque aspect ratio string together the idea that the eight episodes are much more than a simple sitcom. Director Maurice “Mo” Marable, who is known for his work directing 24 episodes of Brockmire and as a collaborator on It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, took influence from vivid feature films— a decision that may have resulted in the distinct appearance the show bears.

“The director, Mo Marable, came with this thing—a lookbook, Knight said.” He would take all of these visuals from other movies, advertisements and photographs, and he would put them in a book together. Some of the movies he came with were Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Sorry to Bother You, Do the Right Thing and Amélie— all really interesting choices. His vision really elevated the material into a fun, funky magical realism. If it was any other director, the show may have not been like that.”

Despite his work being layered in political and societal subtext, Keith Knight’s main goal in Woke, his introduction to television, is to make audiences laugh and then think, which he achieves by deriving comedy from his unique experiences as an African-American artist.

“Tell your story,” Keith said. “Because, if you don’t, someone else will for you. They’ll get it wrong, and you’ll be pissed about it.”

Great article. I will be going through a few of

these issues as well..