The North Carolina Board of Education’s recent decision to change the K-12 history curriculum to discuss racism and the history of marginalized groups in America has been met with controversy, with some calling the new standards “anti-American.”

The curriculum was approved on February 4 in a 7 to 5 vote.

Catherine Truitt, the state superintendent of education, believes that American history courses need to offer diverse perspectives. According to Truitt, students need to learn about topics such as the history of Native Americans, Jim Crow Laws and child labor. To Truitt, it is important that students learn these “hard truths.”

Governor Roy Cooper and several Democratic members of the board believe the curriculum will help students gain a wider view of American history by allowing them to see different perspectives.

“The Governor supports the new standards proposed by educators and believes learning our history accurately is an important part of education,” Dory MacMillan, Roy Cooper’s press secretary, said.

Opponents of the curricular changes believe that educators will now focus too much on the negative parts of American history and not highlight the good.

Board member Todd Chasteen said, “The last thing I want to do is mislead students to think the U.S. is hopelessly bigoted, irredeemable and much worse than most nations—unless that were true, but I don’t believe it is.”

Mark Robinson, the lieutenant governor of North Carolina, also strongly disapproves of the new curriculum.

Robinson created a petition, which currently has over 30,000 signatures, in opposition to the new standards.

“They have serious concerns about these standards. Moving forward with this is irresponsible; we need to go back to the drawing board,” Robinson said of those who signed the petition.

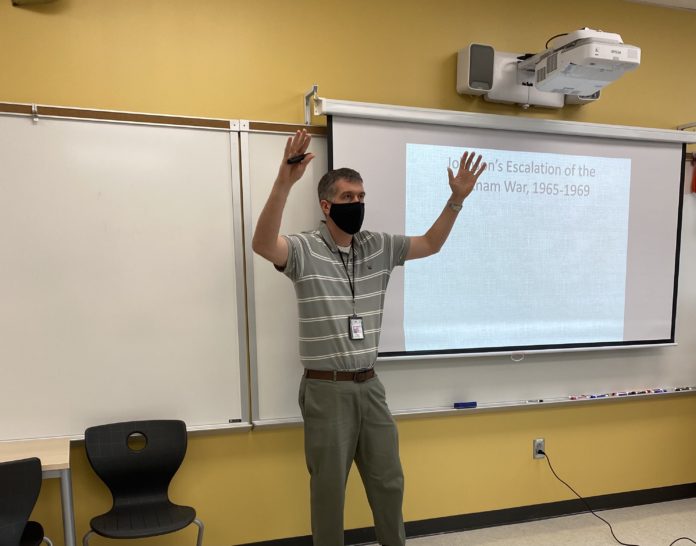

Social studies teacher Matthew North doesn’t believe the argument against the new curriculum holds much merit.

“The idea that these standards are ‘anti-American’ is a politicized statement,” North said. He believes that looking at our country’s past failures, such as slavery or the treatment of minorities, is the key to success.

North’s colleague, history teacher Tim Campbell agrees.

“I think the more people we can include to paint a broader picture of America, the better students can understand what we are as a nation,” he said.

Social studies teacher Anne Beichner sees the revised curriculum as a necessary change.

“It is our responsibility as educators to teach all of our students the truth about historic and present systems of discrimination and oppression so that younger generations can work towards a better future for this country,” Beichner said.

Teachers aren’t the only ones ready to embrace the new curriculum. Students like junior Laura Cai, who is currently taking AP United States History, believe that teaching about oppressed groups in American history is an important step we need to take.

“It shouldn’t be called ‘anti-American’ to simply learn about the mistakes and failures of the American past,” Cai said. “The brutalities that these people faced because of their race shouldn’t be called ‘anti-American’ since it makes up a huge part of American history. Not only does racism affect minorities in the past, but it is also still prevalent today. Americans still face this issue every day.”

Due to opposition from several lawmakers, the state Board of Education is not mandating teachers use the phrases “systematic racism” or “gender identity.”

“The language that we use to discuss these issues matters. It needs to be precise and accurate to ensure that our social studies standards are comprehensive and relevant to all of our students,” Beichner said.

Time can only tell how teachers and students alike will adapt to the controversial K-12 history curriculum.

“A truly strong and resilient society will acknowledge its mistakes and work toward making a ‘more perfect union,’” North said.